Kandukuru Nagarjun, CC BY 2.0

Man pays for a drink with WeChat in Shenzhen

China's WeChat app hit 1 billion monthly users on China's Lunar New Year this February - but before I went to China with Living Research, I had never even heard of it. This was a typical user story for someone who had spent much of their time travelling around the world in nations that weren't China - but once I started to use WeChat, it was hard to stop. To learn more about the nature of WeChat’s seduction, and its effects on China's maker communities, I spoke to makers in Chengdu, Xi'an and Shenzen about their experiences - and learned just as much about our own fantasies of the digital in the UK as I did about those of our Chinese counterparts.

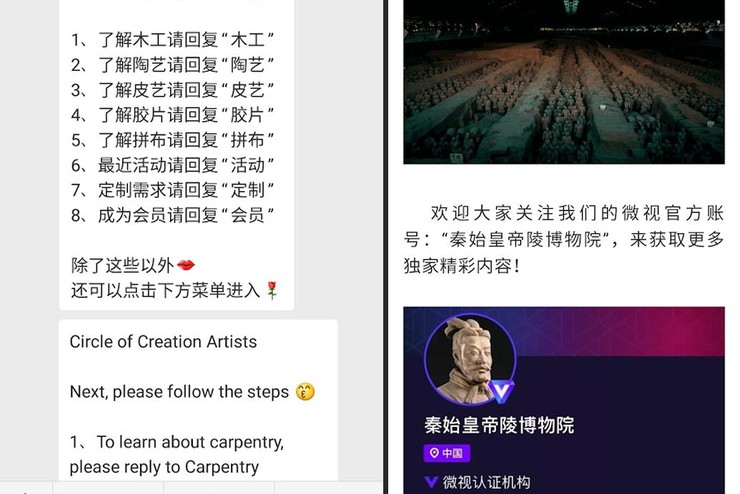

WeChat looks a lot like WhatsApp at first, but with many extra functions that mix features of Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat and other apps banned in China. Topic-oriented chat groups are very popular, where users connect in the thousands with others in their local area. This feature was used heavily by the maker communities we met in China like Niba Makerspace to network, to share code, designs and events, and to engage in novel ways with other technology-focused groups. One maker in Chengdu showed me how she had created two different WeChat user accounts for herself once she hit the maximum groups per user so she could remain active in over 8,000 local maker, craft and business groups. Another maker explained that for him, "WeChat is not just chatting software, it is community... I cannot live without it." WeChat also facilitates direct engagement with companies and organisations through chat bots; I've been in a very energetic conversation with the official WeChat bot of the Mausoleum Museum of the First Emperor of Qin in Shaanxi, for example, which shows no signs of slowing down.

What got me hooked, however, wasn't my friendship with a Terracotta Warrior bot, but WeChat's live-translation possibilities. In China, a nation with a diverse and seemingly endless proliferation of local languages and dialects, translation is a daily necessity - and WeChat allows users to translate their words live, in the moment. Because of this feature, I was able to have many excited micro-interactions with other female makers at the makerspaces we toured who spoke Mandarin or local dialects like Sichuanese, but not English. What would have felt like an unsurpassable barrier elsewhere turned into moments of real connection as our jokes and asides were translated one-to-one, without needing another human as intermediator.

Kat Braybrooke

MakerCircle updates are translated live; Terracotta warrior bot leaves new messages

I'm not the only one who found themselves hooked upon landing in China. WeChat was founded by the Shenzhen corporation Tencent in 2014, and is now the default app used by almost everyone. Its success has been attributed to a variety of factors. In a nation where everything typically had to be paid for by cash, WeChat's 'virtual wallet' has offered a form of consumer liberation, and is used in the vast majority of daily transactions. WeChat also provides users with the creative outlet of stickers, or gifs that they can create and exchange, from excited dumplings to scary baby memes. "Without sharing our emotions without words," a young maker explained, "young people would not be able to communicate! We reflect Chinese popular styles, and create a new kind of culture." WeChat's fortunes were sealed in 2015 when it introduced 'Red Packets', which allowed people to send each other traditional red envelopes full of money through a digital medium for the first time. On the last Chinese New Year, users sent 409,000 red packets to each other in a single second.

WeChat's joys, however, do come with a caveat. Since the Chinese government upgraded its firewall to block WhatsApp last year, it is no secret that the preferred apps in China are sanctioned not only by users, but also by the Party itself. An app will do especially well if it allows user activities to be monitored. It was well known amongst those I spoke to in China that the government logs - and in some cases, deletes - their interactions. According to a recent report, over 170 phrases used on WeChat trigger censorship. However, it was made clear to me that WeChat didn't benefit from any kind of "so-called special way" - having Party members as employees was a common tradition. As a maker explained in Xi'an, "I think [WeChat] will become part of the government’s public administration functions... our resident identity card, medical certificate and file management will probably be managed there." She said this dependency was a "fact of life", not something to fear. "Freedom of speech," I was told by another maker, "is relativistic. Develop cultural creativity first, worry about this after."

Kat Braybrooke

A remixed and censored Terracotta Warrior from the Shùjùxiàn gif-art series

With local administrations such as the government of Guangzhou in the process of creating virtual ID cards through WeChat user accounts, it is perhaps not long before WeChat becomes an unavoidable part of every Chinese citizen's life. Compared to our own data surveillance revelations, is China so different from the U.K.? In both nations, we have chosen to share, learn and create together at the extent of personal freedoms. Perhaps, as makers suggest, we should harness apps like WeChat not to do what is restricted, but instead to do what is encouraged: Build new connections across borders. Maybe then we will be able to envision new ways to gather, to discuss, and to envision a future world where creativity without limits can exist.

Kat explores these ideas further in Shùjùxiàn, a gif-art series for Mozilla’s 2018 Artists Open Web exhibit that reflects on the politics and data traces of WeChat stickers from China and the UK.

The Living Research programme is a partnership between the British Council and the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

In China, the British Council has partnered with MakerNet to co-develop the project in Chengdu and Xi’an.