Azuko

Development conversations in Xinguang Village

Many sectors suffer from ‘jargon-overload’. The international development sector and emerging maker community are no different. Words can help us to be more precise, but they can also become a barrier to honest communication; too technical, too full of their own importance and arguably can discrimate against the poor.

Participatory design is not a new approach, but the buzz around these terms (co-, community-led, impact-driven, humanitarian, human-centred…) is hot. Should we agree on their definitions? Can they be overused? Do they mean the same thing in different places and to different groups?

At AzuKo (an architecture charity serving disadvantaged communities) we believe that true participation, bringing all stakeholders round the table, results in good design. And we believe in supporting communities to lead their own development. For the past four years we’ve been working in the UK and Bangladesh championing this approach.

In March last year, we took part in the Hello Shenzhen residency to explore how maker culture and participatory design could improve life in rural villages. One of the key learnings from our work in Xinguang village on the outskirts of Shenzhen was to remain humble. Can the methods and mindsets we use in our work elsewhere be directly translated? We need to know more.

In November, we set out as explorers. What does ‘community-led’ mean in China?

We wanted to challenge our own assumptions, discover best practice and hear from makers. We connected with communities and designers in Beijing, Henan, Hong Kong, Hunan and Fujian, of Chinese, Taiwanese, English, Irish and French origin.

“Our interviewees are hugely passionate about what they do, often subverting the normal routes to building in favour of less economically focused and more human-centred approaches to design. I have learnt how projects are initiated and conceived, where funding is sourced, how communities are engaged and at what stages. I have listened to their motivations, ambitions, and what matters to them… Nearly all had a story of frustration to tell.”

‘Human-Centred Design in China’, Philippa Battye / AzuKo

We chose to focus on five projects, which offered a range of insights into participatory design in China: Cha'er Hutong Children's Library & Art Centre in Beijing, Xihe Village Cooperative in Henan province, Angdong Health Centre in Hunan province and Fairy Water Village Community Centre and Taoshu Tulou, both in Fujian province. We examined the client, funding and ambition as well as documenting key discoveries which we believe can only be uncovered through visiting a project first-hand and talking with the community directly. Finally, we explored community engagement; the extent to which participatory methods were embedded within the project.

Community-led design and development is the process of working together to create and achieve locally owned visions and goals.

“[Community-led development] is a planning and development approach that’s based on a set of core principles that (at a minimum) set vision and priorities by the people who live in that geographic community, put local voices in the lead, build on local strengths (rather than focus on problems), collaborate across sectors, is intentional and adaptable, and works to achieve systemic change rather than short-term projects.”

The Movement for Defining Community-led Development

There are a multitude of factors which enable or prevent this approach and all the projects we visited exhibited a participatory mentality, to some degree. One in particular stood out.

Throughout the mountainous region of south-eastern Fujian province stand an estimated 3,000 rural earthen dwellings, called 'Tulou'. These fortified circular and square residences function as self-contained village units, towering over the landscape. UNESCO have recognised and are conserving 46, but the remainder are under threat, falling into disrepair and abandoned.

A not-for-profit, called Mei He, led by the inspiring Lin Luson is on a mission to preserve this element of Hakka heritage, one Tulou at a time. He believes the only way is through community-led means. Lin himself grew up in Taoshu Tulou, Neilong (‘Inside Dragon’) and his first project focuses on restoring this very building, which accommodates 30 households.

Azuko

Taoshu Tulou Yunxiao in Fujian Province

The project centres around an all-female community group. With the majority of men working away in nearby towns or as far afield as Shenzhen, it is the women who are the essence of village life. Mei He looks to provide capacity building opportunities for these women, so they can become leaders within their community. This all-female group is responsible for the restoration, maintenance and ultimately the renewed success of Taoshu Tulou.

“We work with a core group. All women. They will take the project forward. For the group to change the mindsets of the villagers, they too need to change. It is a long term engagement.”

Lin Luson

Interestingly the government did not offer support for the project, as they believed the scale and ambition was too big for Mei He to realise. Due to the success of the project (and the press it has received), relationships with local authority are improving, boding well for future engagements.

Lin Luson and Mei He have an ongoing relationship with the community of Neilong. Meetings with the core group are held bi-monthly to help organise the village. This includes discussing any issues with current projects or programmes, as well as identifying needs and exploring new ideas, such as square dancing and drum groups. Conversations centre around building a sustainable future, led by the community.

“In addition to working on new renovation projects, Lin Luson runs extra-curricular courses in the Taoshu Building he grew up in, teaching around 60 school children about tulou architecture and culture in the region. He also hopes to establish a programme that would allow families who moved from their tulou homes to cities to send their children back to live in them during school holidays.”

Saving China’s Abandoned Tulou Homes, Jamie Fullerton / CNN

The Taoshu Tulou project is the closest example of what we recognise as community-led, but all those that we examined shed new light on what works and what doesn’t in China - the barriers to success as well as the key ingredients.

A few insights from all five projects:

- The combination of local skills and knowledge with an ‘outsiders’ perspective e.g. design professionals, encourages innovation. However, balance of power remains key. Those groups which focus on building capacity truly champion communities.

- The role of government within each project differs greatly, with some groups actively opposing government intervention to maintain their ethos, and others welcoming support often leading to significant investment.

- Many of the projects form part of a larger vision for their community, or the wider region. Rural regeneration with a focus on tourism is increasingly commonplace.

- We witnessed a wide range of engagement tools, including semi-structured surveys, focus groups, workshops, prototyping, local construction teams, community coordinators and female-only committees.

Conclusion… community-led design lives in China. It lives through the passion and determination of individuals who mobilise their communities to create change. As in the UK, they face many barriers from financial to a lack of understanding by the powers that be. China is extremely diverse, therefore methods of engagement are unique, driven by culture, community and context. Ultimately their community-led ideals are empowering.

Azuko

Ms Ma explains her clan's history at Fairy Water Village Community centre

“The minorities [women and children] don’t speak out, and no-one speaks for them. Through this project, Ms. Ma has changed her status. Through this project she wants to change people’s perception of what women can do, and show them what they can achieve.”

Yan Gao, Architect discussing Fairy Water Village Community Centre project

After six weeks in country, we were bubbling over with information. We felt a duty to share what we’d heard and witnessed - both within China and beyond its borders. What better platform than during the Shenzhen Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB).

In 2017, for the first time, the event was being held in an urban village called Nantou. Urban villages are increasingly contested (self-governing) neighbourhoods across the city.

“In Shenzhen, urban villages have been the architectural form through which migrants and low-status citizens have claimed rights to the city. Importantly, informal urbanization in the villages has occurred both in dialogue with and in opposition to formally planned urbanization.”

‘Laying Siege to the Villages: Lessons from Shenzhen’, Mary Ann O’Donnell

Azuko

Nantou: Map of the postcard trail

Azuko

Shenzhen Biennale Posters

We wanted visitors to break free from the curated exhibition site to explore the neighbourhood in more depth. In collaboration with our local partner Shenzhen Open Innovation Lab (SZOIL), we took people on a journey through Nantou (and across China).

Azuko

Local Venue Research in Nantou

A trail of postcards with QR codes led people to discover the projects we had visited throughout the country and about community-led approaches to design. QR codes are machine-readable codes for reading by a camera e.g. on a smartphone. These codes are incredibly popular in China which is why we generated our own, so people had access to information about our research.

Azuko

Nantou trail postcards

Azuko

A shop on the postcard trail in Nantou

Azuko

Nantou village resident

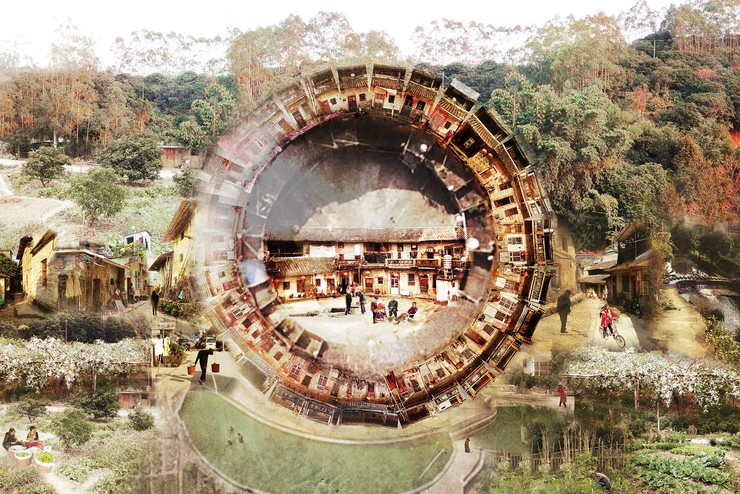

We represented each project through a rich photocollage offering a new perspective, beyond the building, as well as an accompanying insights document.

Azuko

Photocollage Inside Dragon Taoshu Tulou

Although our personal definition of ‘community-led’ might not translate directly and the methods and mindsets may differ, the intention is shared. Let’s not be held back by our words but celebrate their possibilities. Let’s continue to learn from visionaries like Lin Luson, and really listen to the hopes and dreams of communities, giving them a voice for change.

Learn more about the research and download project insights via AzuKo’s website.

Hello Shenzhen is a partnership between the British Council, The Shenzhen Foundation for International Exchange and Cooperation and Shenzhen Open Innovation Lab.

Hello Shenzhen is developed in partnership with Liz Corbin, Institute of Making, UCL

Supported by the Arts and Humanities Research Council

With thanks to Kickstarter for their in-kind support